Stuck in action: why molecular glues could be a game-changer for resolving inflammation

Scientists at the University of Leeds have discovered a new type of molecular glue which was shown to dampen the activation of a key player in inflammation.

Molecular glues are small molecules that promote or enhance interactions between proteins that would not normally bind to each other.

Research in molecular glues is rapidly expanding as they offer an exciting new approach in the design and development of new treatments for diseases, such as autoimmune diseases, cancer and neurogenerative diseases.

Unlike inhibitor drugs which block rogue activity, these molecules act like "adhesives," stabilizing protein-protein interactions to influence biological processes.

One of the difficulties in drug development is that some ideal targets don’t have a clearly defined druggable site. This makes it incredibly difficult to design drugs against, because there’s nowhere for a drug molecule to attach itself to stop rogue activity. So, we need to find another way.

Molecular glue research at the University of Leeds

In a paper published in Nature Structure and Molecular Biology, scientists in the Faculties of Biological Sciences and Medicine and Health in partnership with The Wistar Institute and University of Pennsylvania, reveal a new type of molecular glue which was shown to dampen the activation of an enzyme called BRISC.

BRISC is a key player in inflammation as it’s able to stabilise immune receptors in the active state by preventing their tagging for destruction with ubiquitin chains.

This makes BRISC an attractive target for therapeutic drugs. However, up until now, scientists were unable to intervene in this process, since selective inhibitors are hard to come by.

It was by chance during an initial screening exercise when the research team stumbled across an unknown compound series which functioned as a tiny molecular glue, what scientists coined BRISC molecular glues (BLUEs).

Chemistry synthesis was done at the Wistar institute by Joseph Salvino and colleagues, to further refine BLUEs molecular properties.

Dr. Francesca Chandler, currently a Postdoctoral Research Associate at Queen Mary University London led the study during her PhD in the School of Molecular and Cellular Biology.

This was an incredibly exciting finding at a time when molecular glue research is gaining lots of attention.

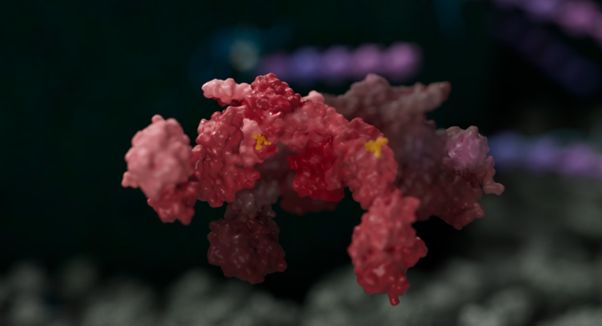

Using structural imaging and biophysics methods, including cryo-electron microscopy and hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry, scientists showed that BLUE compounds can lock two BRISC proteins together.

As a result, the two glued BRISC complexes cannot digest the ubiquitin chains on the immune receptors, which remain available to transmit inflammatory signals driven by interferon, a key molecule involved in autoimmune diseases.

The research team, with help from collaborators at the University of Pennsylvania and Faculty of Medicine and Health in Leeds, then showed BRISC molecular glues could reduce interferon signalling in cells, including those from patients affected by Scleroderma.

This is not only a breakthrough in enabling potential new treatments for autoimmune diseases such as Scleroderma or Lupus, but it also provides an exciting promise for wider molecular glue research.

The challenge of treating inflammation

The research in the field of Systemic Sclerosis as well as other Connective Tissue Diseases like Lupus or inflammatory Myositis has shown that cells from patients have an excessive interferon activation that is associated with the progression of tissue damage. This knowledge has steered current treatments - the first drug blocking interferon is now approved to treat Lupus.

However, interferon is also our primary line of defence against viruses and some forms of cancer, and blocking it entirely increases the risk of viral infections, limiting the use of the drug.

“I was particularly excited to see that BLUEs do not switch off entirely the activity of interferon but they simply “normalise” it.” said Prof. Francesco Del Galdo, Susan Cheney Professor of Experimental Medicine and president of the European Scleroderma Trials and Research network. “In this sense, drugs derived from BLUEs could be used to dim the abnormal activation of cells to a healthy status, instead of switching it off entirely and exposing patients to infections.”

BLUES would therefore be ideal drugs to maintain or re-establish healthy immune responses in patients where the immune system is at cross-wires.